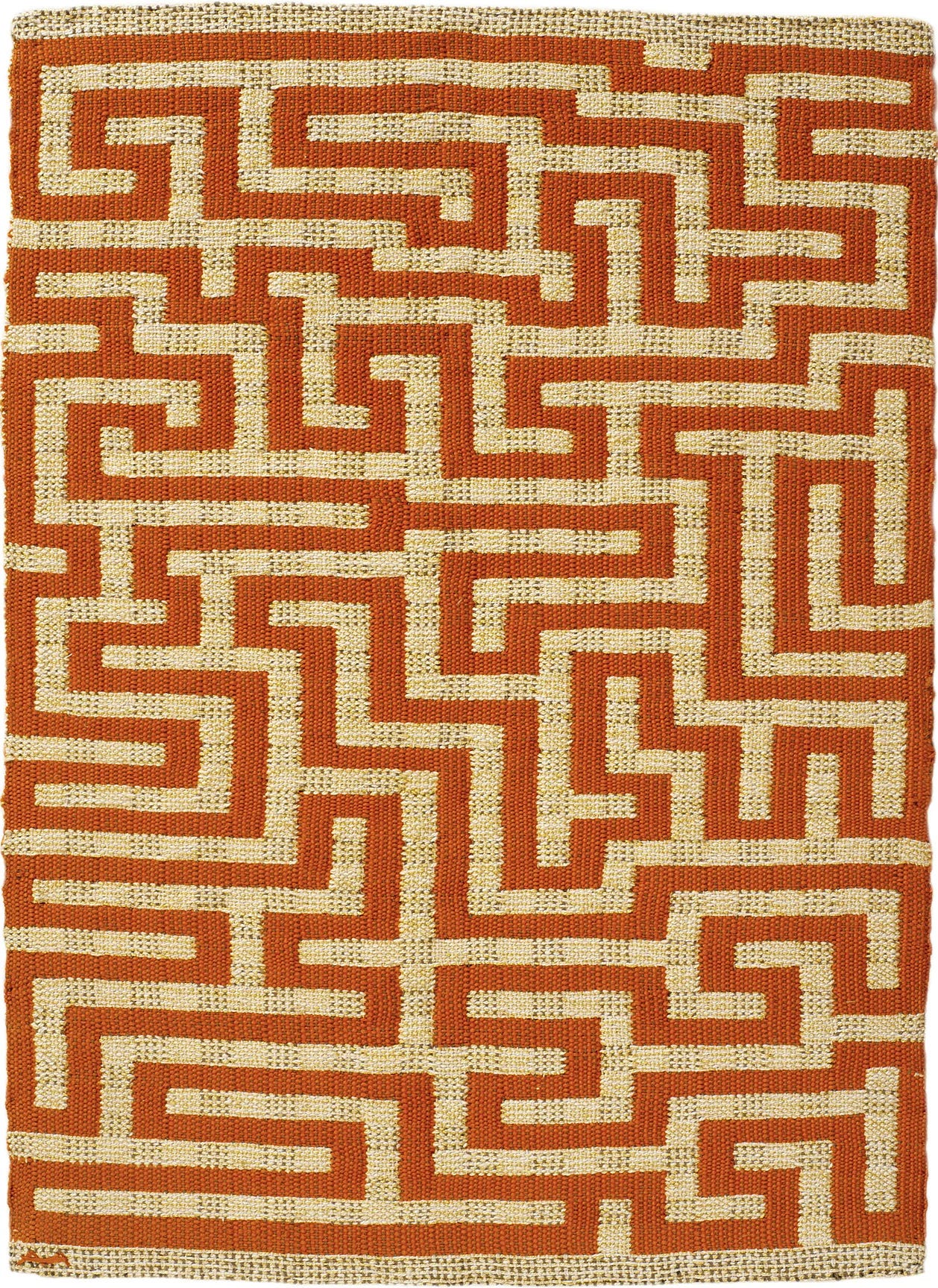

My favorite among Anni Albers’ textile works - not that I’ve seen them all - is Red Meander, from 1954, a striking, geometric tapestry that renders the meander motif in high contrast and texture, alternating strips of warm red and yellow-white. And I think it really is tapestry; that is, tapestry weaving in the technical sense, not in the ‘fashionable, loose sense’, which Albers is at great pains to clarify in her pioneering 1965 book On Weaving.

A student (and, later, a master) at the Bauhaus, then a faculty member at Black Mountain College, Anni Albers must be the most famous and, certainly, is the most important weaver of the 20th century, and possibly ever. (Perhaps the Fates are more significant?) Her book, which I’ve just finished reading, is both a practical guide to weaving and a meditation on craft and art, and it contains a chapter on design that I want to print out and read every night until I’ve memorized it.

On Weaving is mostly concerned, as it should be, with instructing its reader how, and perhaps why, to weave. (It contains a chapter on the history of textile production, and one on weavers’ draft notation.) But Albers doesn’t do anything by half. She advises us not just to weave, but to create, to conceptualize, to design, to execute, and to do so to the best of one’s ability. She suggests that in doing so, one might even create something more meaningful than a useful textile, achieve something higher than just ‘good design’:

Designing usually means ‘giving shape to a useful object’. We do not speak of designing a picture or a concerto, but of designing a house, a city, a bowl, a fabric. But surely these can all be, like a painting or music, works of art. Usefulness does not prevent a thing, anything, from being art. We must conclude, then, that it is the thoughtfulness and care and sensitivity in regard to form that makes a house turn into art, and that it is this degree of thoughtfulness, care, and sensitivity that we should try to attain.

Albers thus places art and craft on a sort of continuum in which a hand-craft, if designed and executed well, can achieve the status of art. Furthermore, she believes that this is exactly what the craftsman should strive for. And it is this attitude that made On Weaving, and Albers herself, so revolutionary - her steadfast conviction that textiles were, or could be, art. “…there are no exclusive materials reserved for art,” she writes, “though we are often told otherwise.”

Albers is clearly enthralled by her craft. She writes about weaving with reverence, humor, and great knowledge, referencing both ancient Peruvian textiles and the most modern weaving methods with clarity and authority. She describes the limitations of the loom, and the ways in which these limits can spark creativity: “…to my mind, limitations may act as directives…Great freedom can be a hindrance because of the bewildering choices it leaves to us, while limitations, when approached open-mindedly, can spur the imagination to make the best use of them and possibly overcome them.”

Elsewhere, Albers emphasizes the importance of structured experimentation, a method she would have learned at the Bauhaus. However, she cautions against novelty for it’s own sake, writing: “Playful invention can be coupled with the inherent discipline of a craft. Our playfulness today often loses its sense of direction, and becomes no more than a bid for attention, rather than a convincing innovation.” Coupling this with her philosophy of design, she urges us towards a practice of focused creative exploration, one which should never decay into ‘formlessness’.

My favorite part of the book is chapter eight, Tactile Sensibility. In it, Albers makes her case for textiles: she writes of the importance of touch, the tactile sense, and the way it can ignite the creative impulse; she describes how fabric can embody different textures and physical qualities, even within the same piece of material, and what this may mean to us. The feeling of a textile is like its color, she says, only more complex; it is “nonfunctional, non utilitarian, and in that respect, like color, it cannot be experienced intellectually. It has to be approached, just like color, nonanalytically, receptively.” I love the idea of really feeling a textile, the way one might look hard at a painting, coming to grips with the material.

I expected to learn a lot about weaving from Anni Albers; what I didn’t expect, and what I find so valuable about this book, is her clear-eyed and emphatic stance on the existential importance of hand-weaving, on the process of making itself. In a few beautiful paragraphs from chapter 8, Albers urges us to encounter raw materials, explore them, and use them to create:

Unless we are specialized producers, our contact with materials is rarely more than a contact with the finished product. … Modern industry saves us endless labor and drudgery; but, Janus-faced, it also bars us from taking part in the forming of material and leaves idle our sense of touch and with it those formative faculties that are stimulated by it.

We touch things to assure ourselves of reality. We touch the objects of our love. We touch the things we form. Our tactile experiences are elemental. If we reduce their range, as we do when we reduce the necessity to form things ourselves, we grow lopsided. We are apt today to overcharge our gray matter with words and pictures - that is, with material already transposed into a certain key, preformulated material, and to fall short in providing for a stimulus that may touch off our creative impulse, such as unformed material, material “in the rough”.

I could quote her endlessly. I took extensive notes as I read this book, reproducing many paragraphs in full. She offers practical commentary on modern life (“Today, we should try to counteract habits that only rarely leave us time to collect ourselves”) and, in the chapter on her philosophy of design, touches on the problems of over-production and over-consumption, abhorring ‘calculated obsolescence’. Always, she writes with clarity and conviction, conveying her meaning with simplicity.

In 1970, five years after the publication of On Weaving, Anni Albers gave up weaving in favor of printmaking, which would be the medium of her art for the rest of her life. Perhaps she had finally tired of the limitations of weaving, but she continued to work with the patterns of cloth, recreating Red Meander as a screenprint:

Searching for more information about Anni Albers, I spent several hours perusing the website of the Josef & Anni Albers Foundation. There I found lectures, articles, photographs of her work (including all of the ones I’ve used here), and some fabulous ones of the artist herself. Her quilted jacket in the image below is giving me all kinds of ideas! I have also linked below some of the articles I found most interesting, and I highly recommend reading them. Some of them were clearly re-written and included in On Weaving, so if you can’t get your hands on the book, they cover some of the same material.

Links:

Handweaving Today: Textile Work at Black Mountain College, 1941

The Smithsonian also has an oral history interview with Anni Albers from 1968, which you can listen to (or read a transcript of) here.

I’ve long wanted to read this. You always help me prioritize my TBR pile!

Thank you for writing about AA. A first attempt at reading the book had me too deep into too many ideas at once. I need to take a slower approach, I think, especially as I have no artistic training.

I am a weaver and a tapestry weaver.

I'm continually beset by the balance between 'utilitarian' and 'art'; does art have to be something that is displayable and therefore that gives it a function? Many weavers I know don't understand what it is to create something pleasing for oneself without the need to offer it out there. They must feel their time is being used usefully rather than mindfully.