Over the past couple of weeks, I’ve done a lot of clothing repair. It seems there is something about a snowstorm that makes me want to tackle my mending pile - and makes my friends give me their garments for repair, too. (I shared a few of these projects last week, but have worked on several more since then.)

I really don’t mind doing repairs for other people, especially friends and family. It’s satisfying to know that I’ve extended the life of a garment whose owner couldn’t do so themselves, and a lot of these projects present interesting challenges that are quite fun to puzzle over. Having mended two puffer coats in the last two weeks, I now consider myself fairly confident in that category of repair (which previously I’d had no experience with).

Visible mending has really surged in popularity lately - and has actually broken into the mainstream - but I find I’m not so interested in that anymore. These days, I like my mends to simply be as neat, effective and unobtrusive as possible, so I mostly stick to good old-fashioned darning and patching, aiming for function and simplicity.

Mending really is old-fashioned, in the sense that it’s a time-honored practice, used all over the world for thousands of years to keep garments in use for as long as possible. The Whitworth Art Gallery, at the University of Manchester, has some incredible medieval Egyptian children’s tunics that were heavily mended about a thousand years ago. My favorite is one that has been darned so much, scarcely any of the original fabric is visible.

Historic menders were very inventive, sometimes splicing the unworn parts of separate garments together to make a new, functional one. The Gunnister man, who was buried in a Shetland bog at the end of the 17th century, wore a pair of knitted stockings whose feet had been completely replaced with other material.

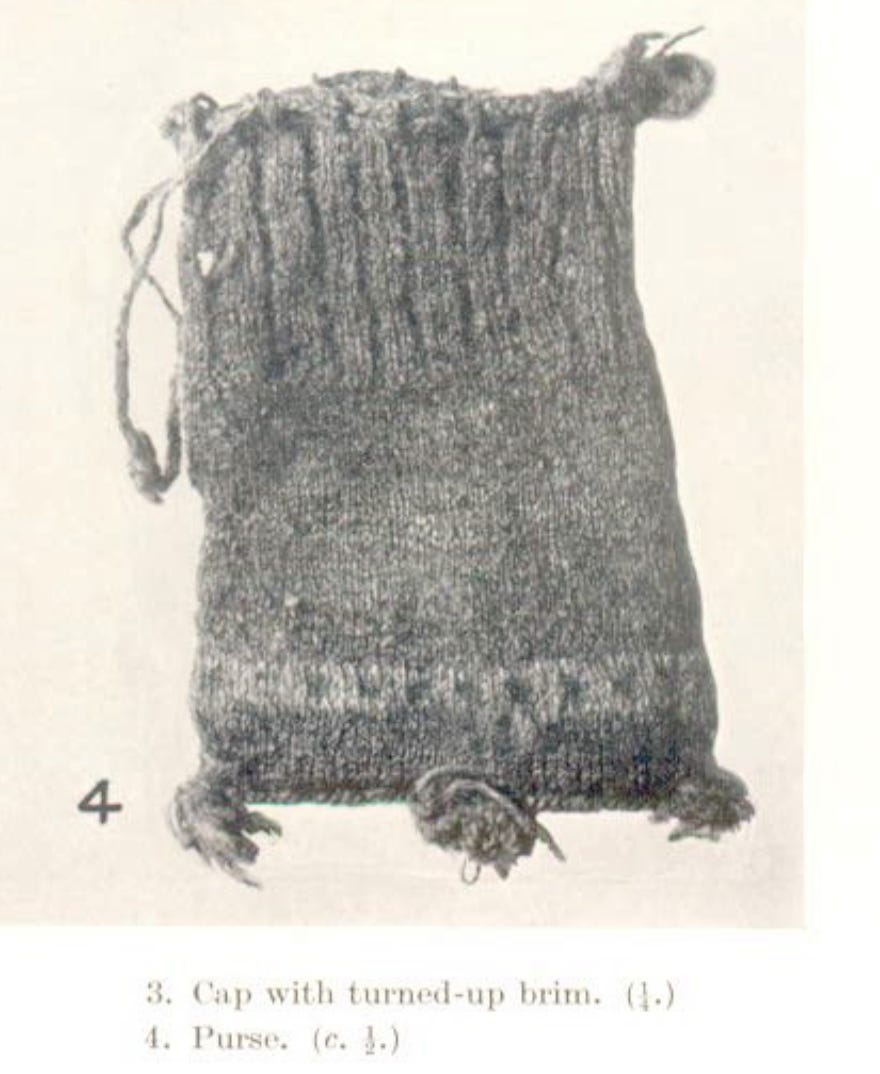

Nearly all of Gunnister Man’s clothing was repaired in some way, with varying degrees of skill. Many of his buttons had been replaced, a tear in the middle of his shirt was roughly stitched together with a tuck, his breeches had been taken in at the waist by five inches, and his knitted gloves were heavily patched. His garments were described in detail in a report made in the Proceedings of the Antiquaries of Scotland after his discovery, which is very interesting reading, especially if you are a knitter. His hat, gloves, stockings and knitted purse are analyzed so thoroughly that they could be recreated entirely, and I’m strongly considering knitting the purse, a jaunty colorwork affair with tassels, which is the oldest example of Fair Isle knitting discovered in Shetland. (One of the authors of this paper, Audrey Henshall, wrote other research papers about historical textiles in Scotland that are well worth reading, if you’re interested in that sort of thing.)

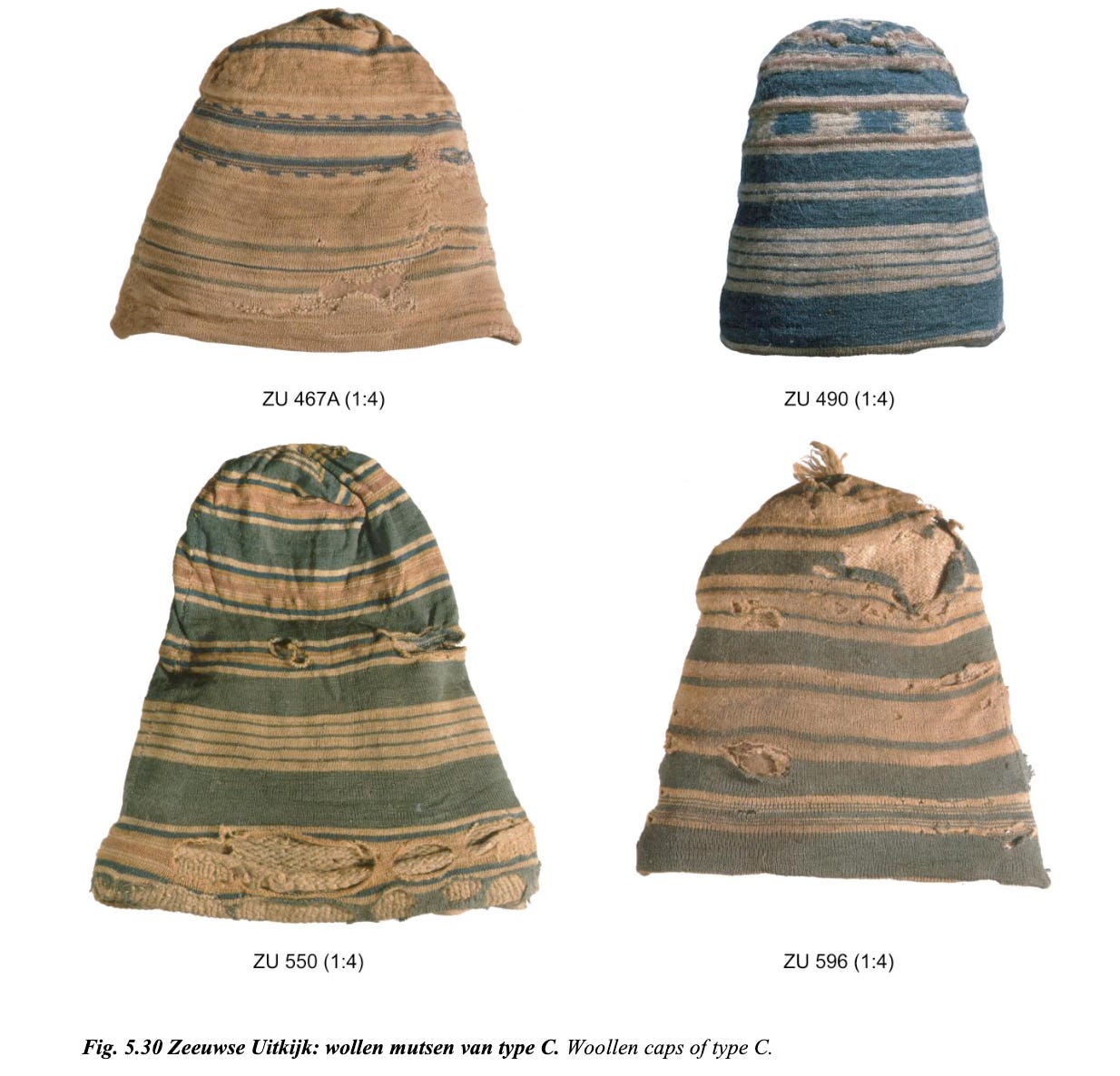

Its quite rare to find historical examples of repaired, working-class clothing like this, as it’s not the sort of thing that was typically deemed worthy of preservation. When a cemetery near a Dutch whaling station in Svalbard was excavated by archaeologists in the 1980s, researchers found that most of the men had been buried in their everyday working clothes (though without any shoes). The excavated graves provide an important glimpse at the everyday clothing of 17th- and 18th-century men, and the summary report from a symposium on the find can be read online (a discussion of the textiles begins on p. 79). As expected, most garments were heavily patched and darned (one jacket had 54 different patches!), and most of the men wore a unique knitted cap, which was apparently very personal.

The hats, some of which have been darned, and all of which are surprisingly modern, are really my favorite. They almost look like 21st-century beanies, and some of them feature sections of colorwork that was clearly created by using tie-dyed yarns:

There is a detailed (500+ page) thesis by Sandra Vons-Comis about these textile finds available online, though most of it is in Dutch; however there is a summary, in English, on page 370 of the pdf. The summary is short but worth reading; again, I found the knitted items to be most fascinating.

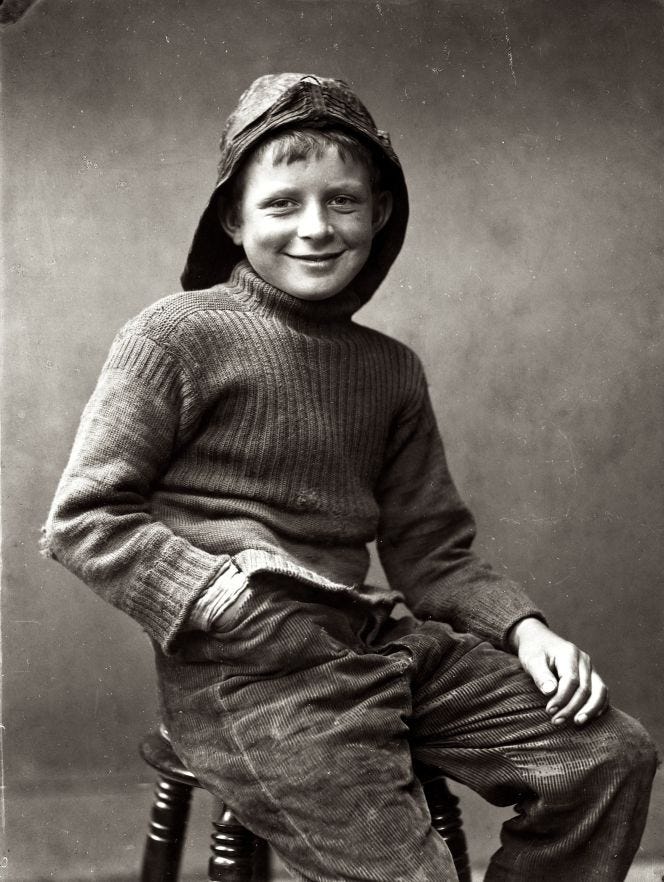

iTextilis, one of my favorite sources, notes in an essay on mending that while the Whitby Museum has only two repaired garments in it’s collection, there are plenty of photographs of working-class people wearing mended clothes. I love the one of a smiling boy in his gansey and corduroys, a tidy darn visible on the front of his jumper. (Presumably his mother hasn’t gotten to the hole in the elbow yet.)

I’m not sure what it is about these old, mended garments that I find so compelling, but I do think they are endlessly fascinating. Probably because they give us an unvarnished look at what life used to be like for the average person. Not many people were living in luxury, wearing richly embroidered satin dressing gowns and slippers - far more would have been working all day, and darning the holes in their socks at night because they couldn’t afford to buy new pairs. It’s a shame that we don’t have more of these garments in our museums.

I tend to repair my clothes because I’m interested in living as sustainably as I can, but I will admit that sentimentality comes into it as well. One of my favorite shirts is an old silk button-up that I thrifted years ago; it’s threadbare in places and has been repaired several times already, but I keep fixing it up because I love it, and I want to keep wearing it. I suppose it’s silly to get deeply attached to one’s clothing, but I seem to do it anyway.

Regardless of why you do it, I do think that repairing things - be it clothes, curtains, or vacuum cleaners - is important. We live in such a wasteful society, which is destroying our planet. We use far more natural resources than we can actually sustain, extracting them in increasingly damaging ways, and then we clog up the environment with our garbage. I’m not a zero-waste person, and I never will be, but I do believe in harm-reduction. Even repairing just a few items of clothing, instead of throwing them away, is beneficial.

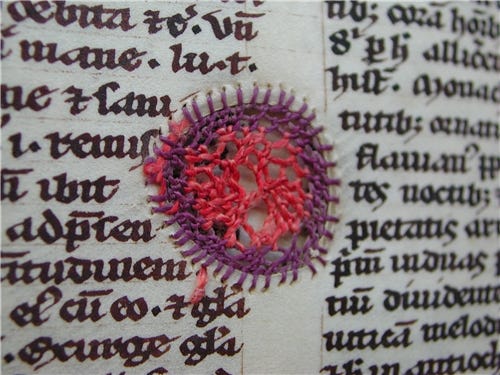

Far from being merely practical, mending can also be an artistic expression of creativity, as evidenced by the recent visible mending movement. And this, too, is not an invention of the modern era - in the course of my research, I stumbled upon a beautiful 14th-century book whose torn parchment pages were repaired with embroidery.

While I acknowledge that the past was never perfect, I do think we can learn from our forebears. Mending has a long, rich history, as both a practical and a decorative art, and I believe it is important to keep this skill alive. There is also so much to discuss and think about when it comes to repair, I’ve barely scratched the surface here.

Well, that’s it from me for now - I’m off to spin more yarn, knit a new hat and do some sewing. I’ll be back next week with a few more thoughts about mending and its cultural importance, both in history and in the modern era. Talk to you soon!

I SHOULD darn all the holes in the cashmere robe, but I never learned how to do it properly, and now the robe is full of patches (cut from other old cashmere things). I'm ready to put the lining in the jacket now, so hopefully there will be pictures on Monday.

I found this fascinating Kelsey, thank you :)