This week, I’m continuing my series on female artists with an essay on Sophie Taeuber-Arp. This is something I plan to carry on with on a monthly basis, focusing mostly on textile and fiber-based artists. Leave a comment to let me know if there is an artist you’d like to see featured in this series!

Sophie Taeuber-Arp was a pioneer of avant-garde dance. A photo of her in costume for a Dada performance in the 19-teens shows her leaning dramatically to the left, arms encased in stiff tubes with claw-like extensions, a startling collage-style mask covering her face. Living in Zurich at the time, she was right at the forefront of the Dada movement. Her ‘abstract dances’ were described as being “…full of flashes and fishbones, of dazzling lights…the figures of her dance are at once mysterious, grotesque, and ecstatic.”1

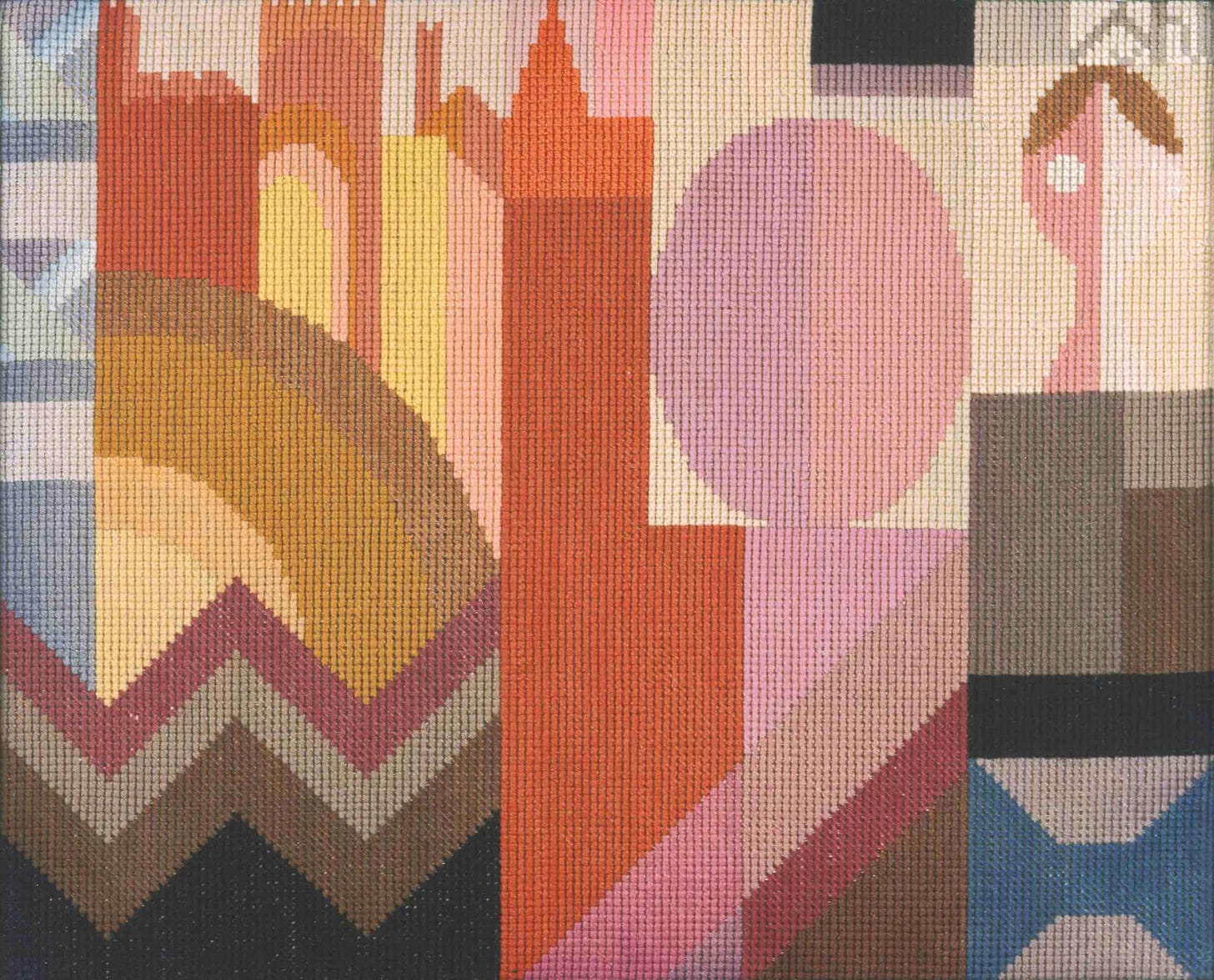

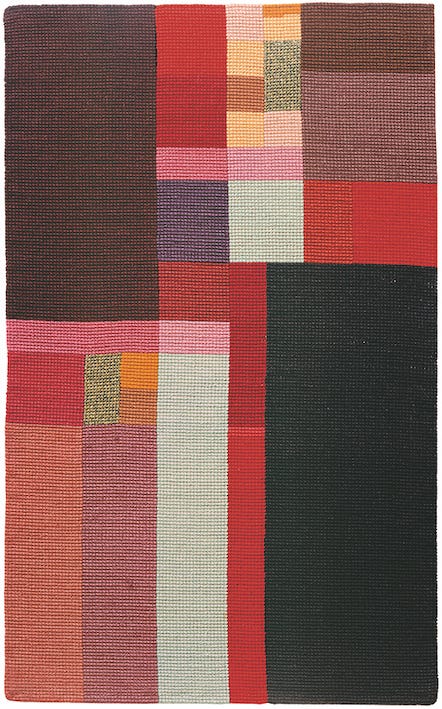

Taeuber-Arp brought this sense of movement to all of her work, and she was prolific in many mediums - including the so-called applied arts. In addition to dance, she was an accomplished painter, sculptor, writer, furniture-maker, interior designer, embroiderer, weaver, and beadworker. As my own interest lies chiefly in textile art, I’m especially drawn to her weavings and needlepoints, which are alive with color and dynamic shapes that seem to shimmer in the air, arrested in a moment of movement.

Anni Albers included two of Taeuber-Arp’s tapestries in her 1965 book On Weaving, and the black-and-white photograph she provides of Formes Biologiques, from 1926, is the only one I’ve been able to find of it on the Internet. It’s a compelling piece, composed of wiggling, irregular motifs on contrasting backgrounds, slightly mellowed by the rich woolly texture of the tapestry. Like Albers, Taeuber-Arp was interested in indigenous art, and some of that influence seems to peep through here.

Born in Switzerland in 1889, Sophie Taeuber-Arp’s mother taught her embroidery, sewing, knitting, and quilting, and the teenage Sophie studied at the St Gallen School of Industrial Design and Crafts. This school was known for its teaching of textile design, and from it she moved to Munich to study at the Teaching and Research Studio for Applied and Fine Arts (a sort of proto-Bauhaus that offered classes in textiles and furniture design). Interestingly, the work of William Morris was deeply influential on both of these institutions, and Taeuber-Arp maintained a life-long, Morris-like dedication to the idea that ‘ornamentation’ and the applied arts had as much value as fine art. Like Morris, she believed that useful things could, and should, also be beautiful.

For most of her life, Taeuber-Arp worked in close collaboration with her husband, Jean Arp - by all accounts, they had a remarkable artistic synergy, each influencing the other’s work. However, Jean Arp didn’t do ‘handwork’, so I’ve chosen to leave him out of this story. Taeuber-Arp’s more design-oriented work, especially in textiles, was unique to her in the context of their relationship.

“Only when we go into ourselves and attempt to be entirely true to ourselves will we succeed in making things of value, living things, and in this way help to develop a new style that is fitting for us.” – Sophie Taeuber-Arp2

Geometric abstraction was the aesthetic language within which Sophie Taeuber-Arp worked, across all of her mediums. Taking inspiration from the organized structure of textiles, she developed a grid-based artistic style and process which is especially vivid in her ‘vertical-horizontal compositions’. Her tapestries and drawings at times feature stylized figures, and she created a stunning sculpture series of Dada heads, but her oeuvre is overwhelmingly non-representational. She was a master of the dynamic line, and her compositions draw the eye all over her canvas (whether it is, in fact, a canvas, or a cushion cover, or a beadwork bag).

I admire the clarity of her vision, which she applied with such precision across so many different art forms. Like Picasso, you can look at any one of her pieces, whether it’s a painting or a tea cozy, and know instantly that it is hers. She considered her necklaces, beaded bags, and cushion covers to be fully part of her artistic practice, which was a fairly radical concept at the time.

For 13 years, Taeuber-Arp was the head of textiles at the Zurich School of Applied Arts, where she focused not only on practical skills, but also taught students the history and theory of ornamental design. In her writings on design, she focused on simplicity and the importance of a deep understanding of materials, prefiguring Anni Albers’ belief that form would follow, or in some ways be created by, function. And like May Morris, she emphasized the need for a point of view: “In a flower, in a beetle, every line, every form, every colour has arisen from a deep necessity.”3

One of the things that I find so interesting about textile artists who work in abstract styles is the way that the texture of a piece becomes magnified - the choice of material is so significant. An abstract painting can be more or less compared to any other abstract painting, materially-speaking - but an abstract woolen tapestry is completely different than an abstract beaded surface or an embroidery in silk thread, for instance. Anni Albers wrote about this in her book, and Sophie Taeuber-Arp explored these ideas throughout her career, as well. Even when working with an ostensibly flat surface, like painted wood, she would carve out or raise certain areas to create her relief sculptures. Images that she created in a painting would often be reproduced in different forms, as well, as if to parse the textural differences.

In 2021, a retrospective of Taeuber-Arp’s work, called Living Abstraction was organized by the Tate Modern, the MoMA and Kunstmuseum Basel. This was an incredibly important exhibition, as Sophie Taeuber-Arp deserves far more recognition as one of the first, and best, abstract artists of the 20th century4. In this exhibition, her work in ‘applied arts’ was shown alongside her ‘fine art’, underscoring the fact that Taeuber-Arp herself did not make those distinctions. Her beaded necklaces were displayed alongside paintings, relief sculptures, even a photograph of the cafe she designed for an entertainment complex in the 1920s. (A full video walkthrough of the exhibit at Kunstmuseum Basel can be found on YouTube - it’s long, but it’s really interesting to watch.)

I’ve not done justice to Taeuber-Arp’s work in this newsletter, as that would be impossible, but I hope I may have piqued your interest. There is a bibliography below and more links in the footnotes. I’ll leave you here for now- talk to you soon!

Additional Reading:

Sophie Taeuber-Arp review – the great overlooked modernist, The Guardian

Biography of Sophie Taeuber-Arp, from the Sophie Taeuber-Arp Research Project

PDF - Review of Living Abstraction

This is a quotation from Hugo Ball, which was reproduced in Dada Dance: Sophie Taeuber’s Visceral Abstraction, Art Journal 73, no. 1 (Spring 2014)

I’m particularly incensed about this because, in the course of researching this piece, I learned that one of her most important paintings is owned by MY local art museum and I have never seen it on display there.

What a wonderful series, Kelsey, and what an amazing artist. Thank you!

Some of your earlier posts inspired me to find Anni Albers' book "On Weaving" at my library, and it's breathtaking. I'm a knitter and poet rather than a weaver, and it's amazing (or not!) how many home truths her book contains about all kinds of making.

Great read! Thank you. I’d like to submit Gunta Stolzl for your list, I just read a fascinating book of her life and work, told through her correspondence.